Describing this project as a journey would be fitting. It goes beyond the physical distance covered (traveling from Canada to Sokoto was indeed an experience!) , but also a personal journey of self-reflection and professional growth for me as a Design researcher and project manager. Being a young woman from Northern Nigeria myself, this initiative held personal significance. Despite the challenges, the excitement and purpose made every obstacle worthwhile in the end.

Our team recently completed a collaborative initiative with UNICEF Nigeria, conducting formative research on social and gender norms in northwestern Nigeria—specifically Sokoto and Katsina states. The ultimate objective was to develop a Social and Behaviour Change (SBC) strategy aimed at reshaping societal perceptions of adolescent girls, fostering girl empowerment within families, promoting balanced family relations, and encouraging positive masculinities. The process involved qualitative and quantitative interviews with adolescent girls and other stakeholders in each state, followed by co-design workshops to share findings and generate intervention ideas. Finally, we drafted SBC strategies outlining norms, their drivers, and key areas for addressing these norms.

Using participatory research methodology as a tool for empowerment:

Prior to kickstarting the field research, we collaborated with the UNICEF Nigeria team to enlist 30 young women aged 18- 27 from each state to join our research team. This move was not just about research; it was a tool for empowerment, equipping these young women with skills in HCD, interviewing techniques, and data analysis. We set out to not just conduct research for the girls, but also with the girls.

This participatory approach did not only serve as an empowerment tool, but it also ensured a comfortable environment for the adolescent girls being interviewed. The peer-to-peer dynamic fostered trust and openness, mitigating the power dynamics that typically occur in an interview setting. To prepare the young women for the field, we conducted an interactive training in both English and Hausa (the native language of the region). Tablets were provided prior to the field research to train the girls on quantitative data collection, and the young women engaged in mock interviews, each taking turns as interviewer/interviewee.

We also used the training sessions as an opportunity to go through the survey and qualitative interview questions with the young women in order to receive their feedback and refine the questions where needed. We wanted to ensure that the young women had a say in what questions were being asked on the field and how said questions were asked as well.

After the training concluded, the girls were given official certificates from the YUX Academy to acknowledge their dedication and also potentially enhance their professional standing.

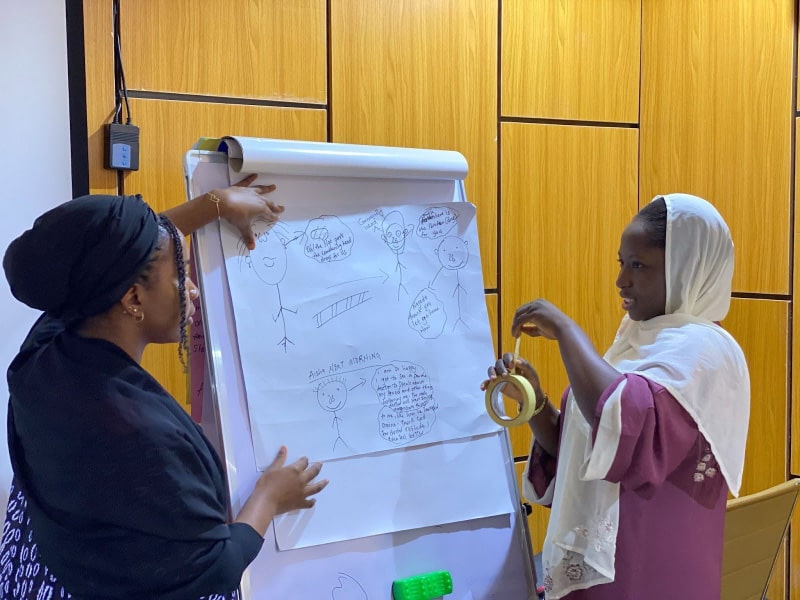

Training the young women in HCD principles, interviewing techniques and data analysis.

Formative Research to Understand Social and Gender Norms in Sokoto and Katsina:

After the training was done, our local team members from YUX, accompanied by the newly integrated young women researchers, ventured into the field to explore gender and social norms affecting adolescent girls in Sokoto and Katsina. For this research, we used a blend of quantitative and qualitative methods. While the quantitative survey exclusively targeted adolescent girls, with the aim of better understanding their experiences and challenges, the qualitative interviews extended to a broader spectrum including caregivers, male siblings, religious and community leaders— influential figures within the girls' ecosystem. We explored two Local Government areas per state.

Our research team!

The field research provided invaluable insights into the various factors hindering the empowerment of adolescent girls in this region. Notable findings include:

- The belief that formal education isn't essential for girls results in families prioritizing marriage and domestic responsibilities over investing in their schooling.

- The negative perception of technology acts as a barrier for girls to own devices and access the internet.

- Due to social and gender norms within the regions, some girls perceive child marriage as beneficial for social status.

- Most male siblings restrain from advocating for their sisters’ rights due to the fear of being scorned and ridiculed.

- Caregivers offer male children greater freedom while imposing restrictions and limiting opportunities for their female children.

Recognizing the benefits of an iterative approach, we chose to initiate the field research in Katsina before progressing to Sokoto. The challenges and corresponding learnings from the Katsina field research informed our subsequent work in Sokoto. Some of these learnings include:

- Planning logistics ahead of time:

While a participatory approach adds significant value to the research process, it does need a lot of planning. Coordinating the logistics on transportation and accommodation for the 30 young women who were involved in the research team was quite challenging. We were committed to ensuring the safety of these young women in the field and their secure return to their respective homes. In addition to the already nuanced situation, logistics planning was not done early due to a misunderstanding on who would be handling what. Hence, we had to figure out a lot of things just a few days before the field research was scheduled to start. Despite the stressful period for both myself and the team, we successfully managed the logistics (many thanks to the local researchers: Rukayat Abdulwaheed, Balkisu Fasani, Yusuf Jamiu, and Lukman Muhammad, who were able to navigate this situation effectively and act fast!). Moving ahead to the Sokoto research, careful planning was carried out well in advance to avoid any further stress.

- Involving local female guides:

An important lesson we learnt from the Katsina field research was the significance of including local female guides, who were well-acquainted with the community and its culture, to accompany the team in the field. The absence of these guides in Katsina posed challenges, particularly during household interviews with adolescent girls and other stakeholders. Despite the inclusion of local young women in the research team and female YUX researchers fluent in the local language, some families were hesitant to allow the research team into their homes. As a result, for the Sokoto field research, we made sure to engage local female guides, such as the daughters of village heads or community leaders, who, possessing a deep understanding of local dynamics, played a crucial role in establishing trust and rapport within households.

- More elaborate consent training for the young women on the research team:

The young women on the research team demonstrated exceptional skills in conducting interviews and fostering comfortable environments for the adolescent girls. However, we observed a less effective consent process. Therefore, in the Sokoto research, we emphasized the significance of consent during our training, providing practical guidance for effective consent collection. Given the sensitive nature of the topics discussed, we also ensured that the young women fully grasped the interviewees' right to withdraw consent at any point, even after the interview had started.

The Co-design Workshops in Sokoto and Katsina:

After concluding the field research in both states, we analyzed the data, in preparation for the co-design workshops. We set out to have 4 workshops per state, two of which would include the adolescent girls, some of whom were interviewed during the field research, and the other two would include the other stakeholders including caregivers, male siblings and community leaders. The sessions were facilitated by the YUX team and, of course, our capable young women who were involved in the field research. Before the workshops, the young women received training in workshop facilitation and were given corresponding certificates afterwards. The idea was to ensure that this initiative took a participatory approach throughout the process and not just in the initial stages.

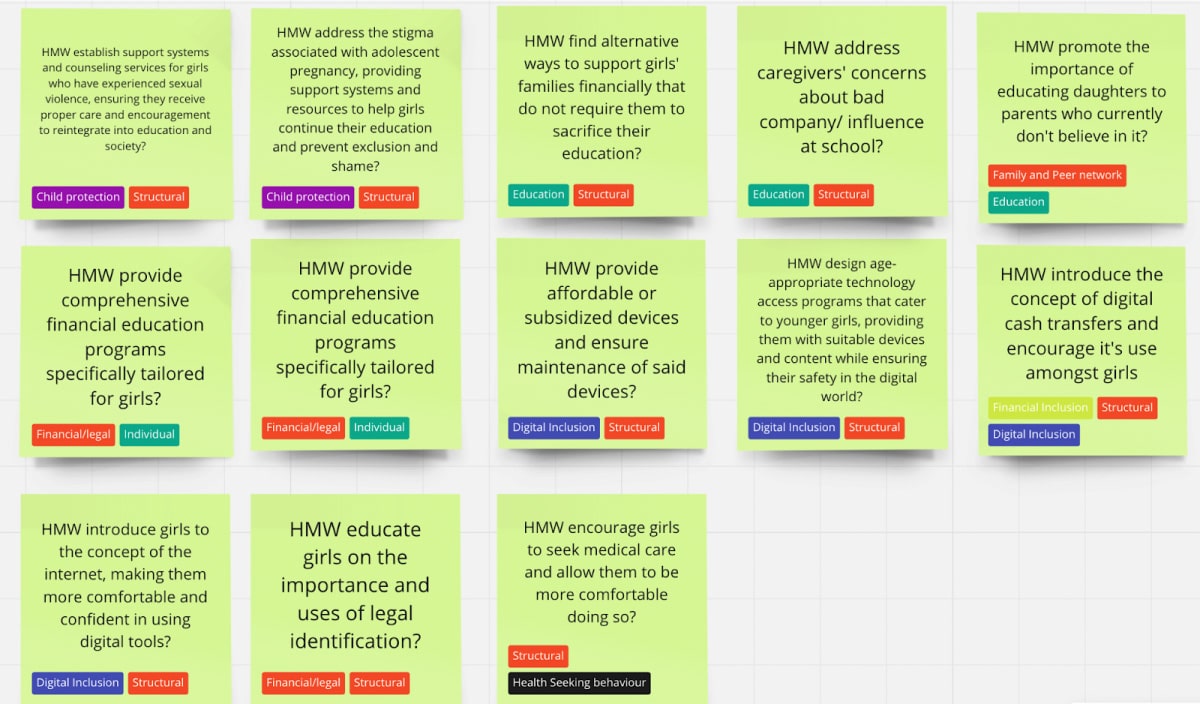

Following the synthesis of data gathered during the data collection phase, the YUX team identified various challenges related to various focus areas including education, health seeking behavior, digital and financial inclusion. These challenges were then accompanied by corresponding "How Might We" (HMW) questions.

Afterwards, a prioritization exercise was conducted collaboratively by the YUX and UNICEF teams to determine the top HMW questions. The HMW questions were prioritized based on the level of impact, feasibility, and clarity for the adolescent girls during brainstorming sessions (i.e., selecting HMW questions that would be readily approachable for girls during workshops). As a result of this process, 13 HMW questions emerged as the highest priority. These 13 HMW questions were then presented to the adolescent girls and stakeholders to work on during the workshops.

Prioritized HMW questions which were presented to the adolescent girls and other stakeholders during the co-creation workshop

In the workshops, the girls were divided into four age-based groups and presented with the 13 "How Might We" (HMW) questions. Each group then voted on the questions most relevant to them. Subsequently, the girls collaborated on formulating potential solutions for the chosen HMW questions and presented them through storyboards within their respective groups. In a later session, during the workshop with other stakeholders, the girls' proposed solutions were showcased, and each stakeholder received a feedback sheet to rate and provide feedback on these solutions. All of these ideas and feedback were then taken into account while drafting the subsequent SBC strategies.

My personal reflections:

As noted earlier, this project led me on a path of self-reflection and professional development. The experiences shared by the girls during interviews and workshops were often really sensitive and quite touching, particularly those revolving around experiences of sexual abuse, ostracization, and stigma. What made it even more disheartening for me was the realization that many of these girls were unaware of alternatives, and perceived these unjust treatments as their norm. Because of the sensitive nature of some of these discussions, I tried to take a step back when necessary throughout the project cycle. However, I could not help but to feel guilty, as it seemed like taking this step back was in some way like a disservice to the young girls who can’t take a break from their reality.

Throughout the project, due to its sensitive nature, detaching myself was challenging. Every drawback seemed like a personal failure to me. This also meant that I took on a lot more than I should have in terms of workload. I’m very thankful to my managers (Camille Kramer-Courbariaux and Yann Le Beux) and team members (Azeezah Adekunle, Rajay Shah, Alexandra Aho, Adama Mbengue, Yash Chudasama & Cumi Oyemike) who were able to recognize this and step in when needed.

As Design researchers, we skillfully weave empathy into our interactions with users, clients, and other stakeholders. However, amidst our dedication to understanding and serving others, we often neglect to extend that same empathy to the most crucial collaborator—ourselves. We need to think of ways to design a balance that nurtures not just innovative solutions but also the well-being of the designers themselves. The question then arises: How can design researchers strike a balance between fostering empathy in their work while also prioritizing their own well-being?

Nevertheless, the meaningful purpose of this project, coupled with our unique approach, turned every obstacle along the way into a worthwhile endeavor. If given the chance, I would gladly embark on this journey again, perhaps with a few tweaks for an even brighter outcome.